|

|

Follow

the compelling journey of Sarah, a 33 year old woman, who discovers she has

HIV. Learn about HIV and AIDS as you explore clinical issues, spiritual,

ethical and legal questions, countertransference, passion and compassion.

Introduction

This course introduces therapists to HIV through the experience of Sarah, a 33 year old woman. Through Sarah's journey I hope you see the relevance of learning about HIV, because Sarah could be almost any adult client, male or female, gay or straight. We will follow Sarah's journey from the suspicion of having HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus, through the anxiety of testing, and her subsequent feelings and actions. In the Internet version of this course, Sarah's comments are in red ink. In Sarah's own words to therapists:

"Tell them--tell everyone! Talk openly to your clients about HIV and AIDS. Educate everyone you know.""We're special, we who have HIV and AIDS. It doesn't matter to me anymore how someone got it, through sex or drugs or blood...the fact is, we are all in it together. We share the same experience, and have the same hopes and dreams. And nobody on this planet gets off alive. It is just that some of us have to look at it sooner. And maybe we're wiser, and maybe not, but judging and being judged doesn't help."

"And ask them, the therapists, to really look themselves in the mirror, and ask themselves if they are judging me. Tell them no healing happens when a person feels judged, and nobody sets out to get HIV or AIDS. Ask them if they judge children for getting measles. I am me, and I have my story, but also I am everyone, every man, every woman, every teenager and every child who has gotten HIV."

"And tell them that life is made up of many storms, big and small. Getting diagnosed HIV+ is a really big storm: a hurricane. And I know that I will have other storms in my life, some big, some small. And if I get AIDS, that will be another hurricane. But tell them that storms pass. They always do!"

| Along the way I will also share my journey as Sarah's therapist. I will share my thoughts, my countertransference reactions, and the spiritual, ethical and legal questions that arose in me. My reactions are in these boxes. |

| I wrote this course because my work with people who have HIV and AIDS has made me more human and more aware of life. Many of us choose death in small ways every day: working in unsatisfactory settings, complaining about things; yet never risking change. We all seem to get too busy. We forget to communicate from our hearts. We don't value the elders and the children in our lives. Working with people living on the edge, who are aware of 'death on their left shoulder'; has made me more conscious, more joyful, and paradoxically, more alive. |

HIV and AIDS are affecting the entire world. Encountering clients such as Sarah, I am reminded once again of the phrase: "Remember, we are not human beings on a spiritual journey, but spiritual beings on a human journey."

I am enormously grateful to Sarah and to other clients and friends who allowed me to share part of their journey. Thank you. This course also wishes to thank the many websites which granted me permission to link. You will find these throughout the text, and in Chapter 10: References and Resources.

Meeting Sarah

Sarah

came to the session extremely anxious. She had not been feeling well

for a few months, following a few days of high fever. "It's just

a flu" she kept telling herself. Still, the lethargy and tiredness

she was experiencing were dragging her down. She wasn't particularly

depressed, although a lack of energy can of course be indicative of depression.

She just didn't feel well. Then she had a series of yeast infections,

stubborn ones that resisted over-the-counter treatments as well as her

gynecologist's prescriptions. She reported that her doctor had mentioned

the possibility of HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus. Dr. Marten had

suggested that Sarah go to the lab at the clinic to be tested, but Sarah

had refused. She had asked her doctor not to put the discussion of the

blood test in her chart, because she was afraid her health insurance would

"What should I do?" She looked to me for guidance.

| For

a therapist, this can be a hard time. If your training, like mine, has

been in non-directive techniques in which we trust that each client

has within him or herself the seeds of wholeness and the potential to make

the right decisions, how do you answer a plea like Sarah's? How do you answer it if you know that Sarah has some risk factors of HIV exposure? What if her actions could be infecting others? Does the Tarasoff case have relevancy when your client does have HIV or AIDS and is not informing his or her partner? Does HIV status have to be disclosed to the client's insurance provider or government agencies? What are the best ways to be supportive and empathic when HIV or AIDS impacts a client and his or her family? These are some of the issues that will be addressed in this course. |

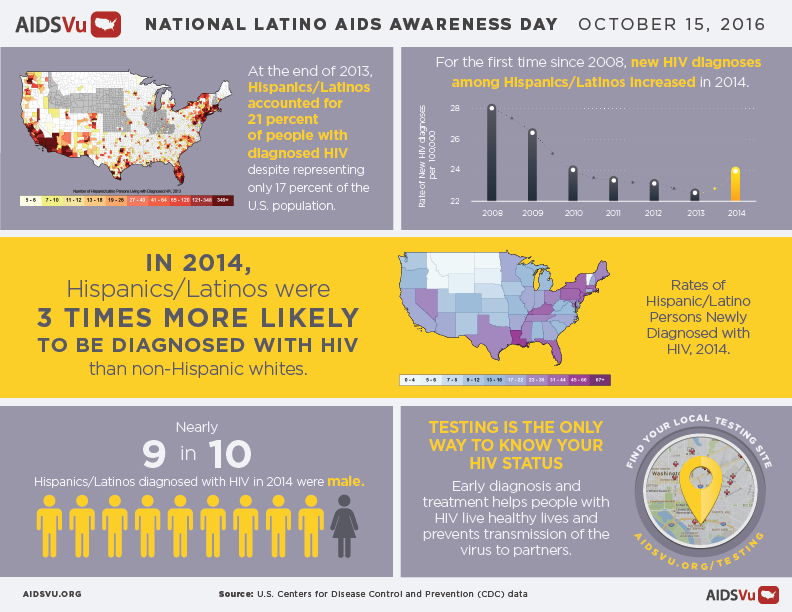

According to the Center for Disease Control:

In 2015, 18,303 people were diagnosed with AIDS. Since the epidemic began in the early 1980s, 1,216,917 people have been diagnosed with AIDS.

In 2014, there were 12,333 deaths (due to any cause) of people with diagnosed HIV infection ever classified as AIDS, and 6,721 deaths were attributed directly to HIV.

Americans are infected with HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus which causes AIDS, the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. HIV impairs the body's ability to fight infections and some cancers by destroying or compromising cells of the immune system. Many of the 1.2 million people affected don't know they have HIV.

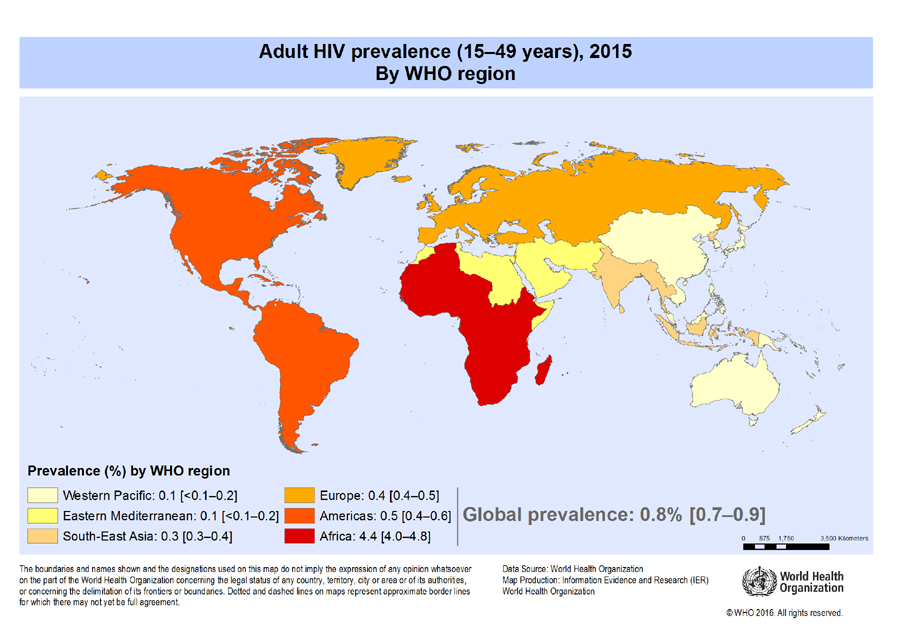

Worldwide, HIV and AIDS are a huge concern. According to UNAIDS:

There were approximately 36.7 million people worldwide living with HIV/AIDS at the end of 2015.

Of these, 1.8 million were children (<15 years old). An estimated 2.1 million individuals worldwide became newly infected with HIV in 2015.

Currently only 60% of people with HIV know their status. The remaining 40% (over 14 million people) still need to access HIV testing services.

World Health Organization (WHO) in November 2016:

Key facts

HIV continues to be a major global public health issue, having claimed more than 35 million lives so far. In 2015, 1.1 (940 000–1.3 million) million people died from HIV-related causes globally.

There were approximately 36.7 (34.0–39.8) million people living with HIV at the end of 2015 with 2.1 (1.8–2.4) million people becoming newly infected with HIV in 2015 globally.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the most affected region, with 25.6 (23.1–28.5) million people living with HIV in 2015. Also sub-Saharan Africa accounts for two-thirds of the global total of new HIV infections.

HIV infection is often diagnosed through rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), which detect the presence or absence of HIV antibodies. Most often these tests provide same-day test results; essential for same day diagnosis and early treatment and care.

There is no cure for HIV infection. However, effective antiretroviral (ARV) drugs can control the virus and help prevent transmission so that people with HIV, and those at substantial risk, can enjoy healthy, long and productive lives.

It is estimated that currently only 60% of people with HIV know their status. The remaining 40% or over 14 million people need to access HIV testing services. By mid-2016, 18.2 (16.1–19.0) million people living with HIV were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) globally.

Between 2000 and 2015, new HIV infections fell by 35%, AIDS-related deaths fell by 28% with some 8 million lives saved. This achievement was the result of great efforts by national HIV programmes supported by civil society and a range of development partners.

Expanding ART to all people living with HIV and expanding prevention choices can help avert 21 million AIDS-related deaths and 28 million new infections by 2030.

How does a person get HIV? Prevalence of HIV/AIDS

This is a world map showing territory size illustrating the proportion of all people aged 15-49 with HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) worldwide, living there.

Sarah's

anxiety increased as the session progressed. She bounced from fear and

panic to a dissociative state, seeming to find no landing place. Her main

sense was that it couldn't possibly happen to her. She kept repeating "I

am not a gay man, I am not an IV drug user, I was never promiscuous...I

just can't believe it." She had flashes of anger at her gynecologist,

Dr. Marten, for suggesting that she be tested. "Who does she think

I am?!!! I will never go back to her!" Sarah has the same misconceptions

of many people. HIV and AIDS have never been conditions exclusive

to the gay or drug using communities. This attitude has prevented many

people from being tested and being treated with compassion. HIV and AIDS

can exist in any community. Sarah

continued to rapidly cycle through a multitude of feelings for the remainder

of the session. She left feeling exhausted and very shaky. We confirmed

our appointment for the following week.

Sarah

came back to therapy the following Tuesday. She described a very rough

week with fear and anxiety. She still had not decided to get tested, but

started to think about her relationships. Could it have been Joe? or Alan?

or even her ex-husband, Stan, who was older than she was and came to the

marriage more experienced sexually than she had been? What about Sam, her

current boyfriend? She described a week in which every twinge in

her body was magnified and she was convinced she was dying. Then, she described

a nightmare:

After

telling me her dream, Sarah began to cry. "I am so scared; so, so scared.

I am scared for Rebecca, that she won't have a mommy..." Here Sarah's tears

turned to sobs. Finally, she looked up at me. "I should get tested, right?" Test Anxiety During

the next week there were several crisis calls from Sarah as she danced

toward, then, away from the idea of HIV testing. In the meantime, her gynecologist,

Dr. Marten, had called, leaving several messages at Sarah's home and work

to call her. Sarah was irate, focusing many of her feelings on Dr. Marten,

rather than on her own fear. On

Tuesday Sarah came to the session. She reported a very stressful week with

difficulty sleeping, increased irritability, shortness with her co-workers

and snapping at Rebecca. She had several more bad dreams, but did not remember

the content.

Finally,

she heaved a sigh. "I am just going to do it, to call the test place and

get a test. I can't stand the not knowing. I am just going to drive myself

crazy if I don't do it!" We discussed the logistics of the test (where

she would go; when; etc.) and Sarah left the session committed to being

tested for HIV.

On

Friday she called to arrange an emergency session. When we met she

said she had gone to the testing site on Thursday and had a panic attack.

She was in the waiting room, having decided on a number for her anonymous

test, when she realized she had chosen Rebecca's birthday. She had gone

to the door to flee when the counselor at the test site appeared. Sarah

was ushered in and given information on HIV, and then her blood was taken

for the test. Sarah would have to wait two weeks and then return. She was

confused, as people often are when they are given information when they

are in shock. She said the counselor talked about 'ELISA' and 'some kind

of blot test' and 'false-positives'.

At

our crisis session she was truly scared. She was having a hard time breathing,

and reported that all she could think about was how stupid she had been,

that she was an idiot, and that if she knew beforehand all the things about

HIV that the counselor had told her, that she would never have had sex,

ever! She would have had Rebecca by artificial insemination from semen

that had been screened for HIV.

She

said every time she looked into her daughter's eyes, all that she could

imagine was that her daughter would have no mother. Sarah learned two extremely important thing

about HIV.

HIV can be in a person's body

for many years with no symptoms. Many carriers of HIV do not

know they have it. "The average amount of time it takes for an HIV positive

person to start showing chronic symptoms is 10 years. With better

treatments, this 10 year average is expected to increase over time." states

Rick Sowadsky MSPH CDS, Senior Communicable Disease Specialist NV AIDS

It can take up to 6 months for

HIV antibodies to appear in the blood. If your clients have had a

potential exposure to HIV or AIDS, it is crucial for them to practice safe

sex and not share IV drug supplies until 6 months after the exposure, and

they have an HIV antibody test that is negative. (Of course, it is prudent

to always practice safe sex and to never share materials contaminated with

blood.) To quote from the HIV Insite web site: Sarah

was increasingly anxious as the time came closer for her HIV test results.

She reported "making several deals with God, such as 'I will never

lose my temper again with Rebecca if I am OK'" and looking for signs everywhere.

"If I saw a hummingbird, that was a good sign. If the light turned

red before I got to the intersection, that was a bad sign." Sarah

went back two weeks after her test and was told that her first test was

positive, but that routinely a second, more accurate test was given to

rule out false positives. Sarah again was seen for an emergency session,

and began again the dance of denial and dissociation, coupled with great

fear.

The first test given is usually

the ELISA, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. If this is positive,

the Western Blot test is administered. Generally, a person is considered

HIV positive only if both tests are positive. This is considered

accurate 98% of the time.

Finding a Place to Get Tested for HIV Your doctor or other healthcare provider can test you for HIV or tell you where you can get tested. Or, the following resources can help you find a testing location: HIV Testing and Care Locator, locator.aids.gov Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1-800-232-4636 (toll-free) or gettested.cdc.gov Drugstores sell home testing kits The only way to know for sure whether you have HIV is to get tested.

CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested

for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. Knowing your HIV

status gives you powerful information to help you take steps to keep you

and your partner healthy. This section answers some of the most common

questions related to HIV testing, including the types of tests

available, where to get one, and what to expect when you get tested.

CDC recommends that everyone

between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part

of routine health care. About 1 in 8 people in the United States who

have HIV don’t know they have it. People with certain risk factors should get tested more often. If you

were HIV-negative the last time you were tested and answer yes to any

of the following questions, you should get an HIV test because these

things increase your chances of getting HIV:

You should be tested at least once a year if you keep doing any of

these things. Sexually active gay and bisexual men may benefit from more

frequent testing (for example, every 3 to 6 months). If you’re pregnant, talk to your health care provider about getting

tested for HIV and other ways to protect you and your child from getting

HIV. Also, anyone who has been sexually assaulted should get an HIV

test as soon as possible after the assault and should consider post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), taking antiretroviral medicines after being potentially exposed to HIV to prevent becoming infected. Before having sex for the first time with a new partner, you and your

partner should talk about your sexual and drug-use history, disclose

your HIV status, and consider getting tested for HIV and learning the

results. Learn more about how to protect yourself, and get information tailored to meet your needs from CDC’s HIV Risk Reduction Tool How can testing help me?

The only way to know for sure whether you have HIV is to get tested.

Knowing your HIV status gives you powerful information to help you take steps to keep you and your partner healthy. If you test positive, you can take medicine to treat HIV to stay

healthy for many years and greatly reduce the chance of transmitting HIV

to your sex partner. If you test negative, you have more prevention tools available today to prevent HIV than ever before. If you are pregnant, you should be tested for HIV so that you can

begin treatment if you’re HIV-positive. If an HIV-positive woman is

treated for HIV early in her pregnancy, the risk of transmitting HIV to

her baby can be very low. I don't believe I am at high risk. Why should I get tested?

Some people who test positive for HIV

were not aware of their risk. That’s why CDC recommends that everyone

between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part

of routine health care. Even if you are in a monogamous relationship (both you and your

partner are having sex only with each other), you should find out for

sure whether you or your partner has HIV. See Should I get tested for HIV? to learn more about who is at high risk for HIV and should be tested more often. I am pregnant. Why should I get tested?

All pregnant women should be tested

for HIV so that they can begin treatment if they’re HIV-positive. If a

woman is treated for HIV early in her pregnancy, the risk of

transmitting HIV to her baby can be very low. Testing pregnant women for

HIV infection and treating those who are infected have led to a big

decline in the number of children infected with HIV from their mothers. The treatment is most effective for preventing HIV transmission to

babies when started as early as possible during pregnancy. However,

there are still great health benefits to beginning preventive treatment

even during labor or shortly after the baby is born. There are three broad types of

tests available: antibody tests, combination or fourth-generation

tests, and nucleic acid tests (NAT). HIV tests may be performed on

blood, oral fluid, or urine. Most HIV tests, including most rapid tests and home tests, are antibody tests.

Antibodies are produced by your immune system when you’re exposed to

viruses like HIV or bacteria. HIV antibody tests look for these

antibodies to HIV in your blood or oral fluid. In general, antibody

tests that use blood can detect HIV slightly sooner after infection than

tests done with oral fluid. With a rapid antibody screening test, results are ready in 30 minutes or less. The OraQuick HIV Test, which involves taking an

oral swab, provides fast results. You have to swab your mouth for an

oral fluid sample and use a kit to test it. Results are available in 20

minutes. The manufacturer provides confidential counseling and referral

to follow-up testing sites. Because the level of antibody in oral fluid

is lower than it is in blood, blood tests find infection sooner after

exposure than oral fluid tests. These tests are available for purchase

in stores and online. They may be used at home, or they may be used for

testing in some community and clinic testing programs. The Home Access HIV-1 Test System is a home

collection kit, which involves pricking your finger to collect a blood

sample, sending the sample by mail to a licensed laboratory, and then

calling in for results as early as the next business day. This test is

anonymous. The manufacturer provides confidential counseling and

referral to treatment. If you use any type of antibody test

and have a positive result, you will need to take a follow-up test to

confirm your results. If your first test is a rapid home test and it’s

positive, you will be sent to a health care provider to get follow-up

testing. If your first test is done in a testing lab and it’s positive,

the lab will conduct the follow-up testing, usually on the same blood

sample as the first test. A combination, or fourth-generation, test looks

for both HIV antibodies and antigens. Antigens are foreign substances

that cause your immune system to activate. The antigen is part of the

virus itself and is present during acute HIV infection (the phase of

infection right after people are infected but before they develop

antibodies to HIV). If you’re infected with HIV, an antigen called p24

is produced even before antibodies develop. Combination screening tests

are now recommended for testing done in labs and are becoming more

common in the United States. There is now a rapid combination test

available. A nucleic acid test (NAT) looks for HIV in the

blood. It looks for the virus and not the antibodies to the virus. The

test can give either a positive/negative result or an actual amount of

virus present in the blood (known as a viral load test). This test is

very expensive and not routinely used for screening individuals unless

they recently had a high-risk exposure or a possible exposure with early

symptoms of HIV infection. Talk to your health care provider to see what type of HIV test is right for you. After you get tested, it’s important for you to find out the result

of your test so that you can talk to your health care provider about

treatment options if you’re HIV-positive. If you’re HIV-negative,

continue to take actions to prevent HIV, like using condoms the right way every time you have sex and taking medicines to prevent HIV if you’re at high risk.

No HIV test can detect HIV

immediately after infection. If you think you’ve been exposed to HIV,

talk to your health care provider as soon as possible. The time between when a person gets HIV and when a test can accurately detect it is called the window period. The window period varies from person to person and also depends upon the type of HIV test.

Most HIV tests are antibody tests. Antibodies are

produced by your immune system when you’re exposed to viruses like HIV

or bacteria. HIV antibody tests look for these antibodies to HIV in your

blood or oral fluid. A combination, or fourth-generation, test looks

for both HIV antibodies and antigens. Antigens are foreign substances

that cause your immune system to activate. The antigen is part of the

virus itself and is present during acute HIV infection (the phase of

infection right after people are infected but before they develop

antibodies to HIV). A nucleic acid test (NAT) looks for HIV in the

blood. It looks for the virus and not the antibodies to the virus. This

test is very expensive and not routinely used for screening individuals

unless they recently had a high-risk exposure or a possible exposure

with early symptoms of HIV infection. Ask your health care provider about the window period for the test

you’re taking. If you’re using a home test, you can get that information

from the materials included in the test’s package. If you get an HIV

test within 3 months after a potential HIV exposure and the result is

negative, get tested again in 3 more months to be sure. If you learned you were HIV-negative the last time you were tested,

you can only be sure you’re still negative if you haven’t had a

potential HIV exposure since your last test. If you’re sexually active,

continue to take actions to prevent HIV, like using condoms the right way every time you have sex and taking medicines to prevent HIV if you’re at high risk. Learn(https://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/male-condom-use.html) the right way to use a male condom. A negative result doesn’t necessarily

mean that you don't have HIV. That's because of the window period— the

time between when a person gets HIV and when a test can accurately

detect it. The window period varies from person to person and is also

different depending upon the type of HIV test. (See How soon after an exposure to HIV can an HIV test detect if I am infected?) Ask your health care provider about the window period for the test

you’re taking. If you’re using a home test, you can get that information

from the materials included in the test’s package. If you get an HIV

test within 3 months after a potential HIV exposure and the result is

negative, get tested again in 3 more months to be sure. If you learned you were HIV-negative the last time you were tested,

you can only be sure you’re still negative if you haven’t had a

potential HIV exposure since your last test. If you’re sexually active,

continue to take actions to prevent HIV, like using condoms the right way every time you have sex and taking medicines to prevent HIV if you’re at high risk. Learn(https://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/male-condom-use.html) the right way to use a male condom.

No. Your HIV test result reveals only your HIV status. HIV is not necessarily transmitted every time you have sex.

Therefore, taking an HIV test is not a way to find out if your partner

is infected. It’s important to be open with your partners and ask them to tell you

their HIV status. But keep in mind that your partners may not know or

may be wrong about their status, and some may not tell you if they have

HIV even if they know they’re infected. Consider getting tested together

so you can both know your HIV status and take steps to keep yourselves

healthy.

A follow-up test will be conducted. If the follow-up test is also positive, it means you are HIV-positive. If you had a rapid screening test, the testing site will arrange a

follow-up test to make sure the screening test result was correct. If

your blood was tested in a lab, the lab will conduct a follow-up test on

the same sample. It is important that you start medical care and begin HIV treatment

as soon as you are diagnosed with HIV. Anti-retroviral therapy or ART

(taking medicines to treat HIV infection) is recommended for all people

with HIV, regardless of how long they’ve had the virus or how healthy

they are. It slows the progression of HIV and helps protect your immune

system. ART can keep you healthy for many years and greatly reduces your

chance of transmitting HIV to sex partners if taken the right way,

every day. If you have health insurance, your insurer is required to cover some

medicines used to treat HIV. If you don’t have health insurance, or

you’re unable to afford your co-pay or co-insurance amount, you may be

eligible for government programs that can help through Medicaid,

Medicare, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, and community health centers.

Your health care provider or local public health department can tell

you where to get HIV treatment. To lower your risk of transmitting HIV, Receiving a diagnosis of HIV can be a life-changing event. People can

feel many emotions—sadness, hopelessness, and even anger. Allied health

care providers and social service providers, often available at your

health care provider’s office, will have the tools to help you work

through the early stages of your diagnosis and begin to manage your HIV. Talking to others who have HIV may also be helpful. Find a local HIV

support group. Learn about how other people living with HIV have handled

their diagnosis.

No. Being HIV-positive does not mean

you have AIDS. AIDS is the most advanced stage of HIV disease. HIV can

lead to AIDS if not treated.

If you take an anonymous test,

no one but you will know the result. If you take a confidential test,

your test result will be part of your medical record, but it is still

protected by state and federal privacy laws. With confidential testing, if you test positive for HIV, the test

result and your name will be reported to the state or local health

department to help public health officials get better estimates of the

rates of HIV in the state. The state health department will then remove all personal information about you (name, address, etc.) and share the remaining non-identifying

information with CDC. CDC does not share this information with anyone

else, including insurance companies.

It’s important to share your status with your sex partners. Whether you disclose your status to others is your decision. Partners Many resources can help you learn ways to disclose your status to

your partners. For tips on how to start the conversation with your

partners, check out CDC’s Start Talking(https://www.cdc.gov/actagainstaids/campaigns/starttalking/index.html) campaign. If you’re nervous about disclosing your test result, or you have been

threatened or injured by your partner, you can ask your doctor or the

local health department to tell them that they might have been exposed

to HIV. This is called partner notification services. Health departments

do not reveal your name to your partners. They will only tell your

partners that they have been exposed to HIV and should get tested. Many states have laws(https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/exposure.html) that require you to tell your sexual partners if you’re HIV-positive

before you have sex (anal, vaginal, or oral) or tell your drug-using

partners before you share drugs or needles to inject drugs. In some

states, you can be charged with a crime if you don’t tell your partner

your HIV status, even if your partner doesn’t become infected. Family and friends If you are under 18, however, some states allow your health care

provider to tell your parent(s) that you received services for HIV if

they think doing so is in your best interest. For more information, see

the Guttmacher Institute’s State Policies in Brief: Minors’ Access to STI Services. Employers If you have health insurance through your employer, the insurance company cannot legally tell your employer that you have HIV. But it is possible that your

employer could find out if the insurance company provides detailed

information to your employer about the benefits it pays or the costs of

insurance. All people with HIV are covered under the Americans with Disabilities

Act. This means that your employer cannot discriminate against you

because of your HIV status as long as you can do your job. To learn

more, see the Department of Justice’s website.

HIV screening is covered by health

insurance without a co-pay, as required by the Affordable Care Act. If

you do not have medical insurance, some testing sites may offer free

tests. See Where can I get tested? for more information.

If you have health insurance, your

insurer is required to cover some medicines used to treat HIV. If you

don’t have health insurance, or you’re unable to afford your co-pay or

co-insurance amount, you may be eligible for government programs that

can help through Medicaid, Medicare, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program,

and community health centers. Your health care provider or local public

health department can tell you where to get HIV treatment. See The Affordable Care Act and HIV/AIDS for more information. Sarah

came to the next session deeply shaken. Her second HIV test, the

Western Blot, was also positive. She was in shock. Her feelings

and moods again took on the quality of being on a roller coaster.

"I feel awful, like my guts are torn out. I feel really scared, really

sad. I feel like I am in a little boat, or no boat at all, and there

is a huge storm all around me. It is so empty inside me right now.

It is horror, horror, horror." I began my own process of

grief. I asked for the help of Kuan Yin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion,

to help me hold Sarah's pain and grief. Her name means "She Who Hearkens

to the Cries of the World". She is also known as Quan Yin, Kannon,

Avalokitesvara, Miao Shan and Tara.

Here she is depicted with

a bottle, pouring out her endless compassion and mercy on us all. One story of Kuan Yin states that she was on the threshold of

Nirvana when she heard the cries of human pain. She (or He; Kuan Yin is

sometimes referred to as male) stopped and would not cross. She will stay

with us until all the tears have been shed. I was remembering Mike, a

dear friend who died of AIDS. Mike was a therapist, an MFCC, who got AIDS

from his lover, Alan. Mike was afraid to be tested for HIV when Alan was

diagnosed. He said he would rather not know. In retrospect, it seems

that he did know that he too was HIV positive. Mike's first signs were

sores on his skin, which he ignored. Mike knew about KS, Kaposi's Sarcoma,

as one of the signs of AIDS. Mike was finally diagnosed about two years

after Alan's death, when a troublesome cough turned out to be pneumocystis

carinii pneumonia (PCP), a type of pneumonia that is an 'Indicator Illness'

of AIDS. Sarah's

grief was very deep and very real. She was mourning not only her diagnosis, but also the loss of her future. She continued to swing between shock

and grief in this session and the next several sessions. There

is help out there.

It will

get better.

Legal and Ethical

Issues Sarah

had to deal with external realities in addition to her internal states.

Since she didn't know when she contracted HIV, she was very afraid that

her daughter Rebecca might also have it. Early in her pregnancy Sarah had

been tested for HIV, as part of the routine blood work she received at

the clinic where she went for prenatal care. In California, prenatal check-ups

regularly include HIV testing, because administration of medication (currently

zidovudine- ZDV or AZT) during pregnancy, labor and delivery and for the

first six weeks of the infant's life can often prevent mother-to-fetus

transmission of the virus. So, while Sarah knew she did not have HIV early

in her pregnancy, she did not know if she had been infected during pregnancy. Sarah had

been counseled regarding "partner notification" when she received her positive

diagnosis, but so far she had been unable to do anything about it. She had the

look of shock and horror, the DSM diagnosis of "looking like a deer in the headlights

syndrome". Your state health department will then remove all of your personal information (name, address, etc.) from your test results and send the information to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC is the Federal agency responsible for tracking national public health trends. CDC does not share this information with anyone else, including insurance companies. For more information, see CDC’s Questions about Privacy, Insurance, and Cost.

3. HIV was transmitted through

blood transfusions prior to 1985. Since then, the U.S. blood supply has

been screened for HIV and heat treatment has been used to destroy HIV in

the blood supply. Many hemophiliacs have died of AIDS from contaminated

blood components, although now these products are being screened.

4. HIV has been transmitted

to health care workers who have received accidental needle sticks.

5. HIV can be transmitted

from an infected mother to her child, during pregnancy, labor, delivery

and through breast feeding. An infant can be born HIV positive.

While saliva has not been

found to contain significant amounts of HIV, oral/genital sexual contact

can be risky if there are small open sores, so use of latex protection

is recommended.

HIV Among People Aged 50 and Over

People aged 55 and older accounted for 26% of all Americans living with diagnosed or undiagnosed HIV infection in 2013.

http://www.worldmapper.org/

How

do we best help Sarah at this point? Although this course will follow Sarah's

treatment, it also addresses the treatment issues of other women, men and

children that are HIV positive or have AIDS. While we follow 33 year old

Sarah in her journey, some of what is described also applies to 17 year

old Carlos, 59 year old Jan, 41 year old Peter, to the parents of Eleanor,

aged 7 months, and to many many others facing HIV and AIDS. All names and

identifying details have been changed to ensure confidentiality.

Where

do I go with Sarah at this point in the session? Do I educate her about

HIV transmission? Do I try to connect with the part of her that is

terrified, or that is angry at the doctor? Do I try to reassure her?

What should I do?

I had been working with

Sarah for slightly less than a year. She had started therapy to resolve

relationship issues, having had a series of what she called "bad boyfriends",

men was dating after a brief first marriage. Sarah was the mother of six

year old Rebecca and was in a relationship with Sam, whom she hoped to

marry.

Sarah was monogamous in

each relationship, as were the boyfriends, to the best of her knowledge.

Sarah had never used drugs

intravenously, or shared drug paraphernalia ('cookers' or 'cotton'; apparatus

for cooking and straining drugs.)

Sarah had not received a

blood transfusion.

Sarah had never been sexually

assaulted.

I decided to follow Sarah

in her process at this point, not to educate her regarding HIV transmission,

but to see where she would go. I was able to do this because Dr. Marten

had already raised the issue of HIV testing with Sarah. I could see that

if I joined with Dr. Marten at this point in the therapy, there was a possibility

that neither Dr. Marten nor I would ever see Sarah again.

I

took a good look at myself when Sarah left. I was frightened for her and

frightened that her story could be my story or the story of almost any

woman that I knew. I wondered if that thought was homophobic, because

it could also be the story of most men too. We all want love and sometimes

where we find it has repercussions.

I was scared at another

level because in the early 1980's I volunteered for an organization called

"The Shanti Project", which was run out of a small house in Berkeley. I

remember hearing about a thing called "The Gay Cancer", knowing men who

had these sores called KS (Kaposi's Sarcoma) and watching them die one

by one. Over the years the illness these people had became known as AIDS,

the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. A lot of my friends died. Was

I suffering from post traumatic stress disorder or compassion fatigue,

having been near the front lines of the epidemic?

Did I have the heart to

go on Sarah's journey wherever it would lead?

'I

dreamed I was with Rebecca, my daughter, at the beach. We are sunbathing,

and there is a shadow on my striped beach towel. I look up, and there is

a huge spider between me and the sun. I grab Rebecca and we try to run,

but I can't run in the sand. I wake up and am very scared. I am sweating.

I

sat silently with Sarah at this point, knowing that sometimes the best

words are no words. I knew that she was already using latex

condoms, both for birth control and to try to control her repeated yeast

infections.

My decision to wait a bit

for Sarah's internal process to catch up with the external process (in

her case the symptoms she was experiencing, and her doctor's recommendation

that she be tested) allowed me a luxury that the therapist doesn't always

have. Imagine for a moment that Sarah is your client:

What would you do?

Supposing Sarah was an IV

drug user...would you do anything different?

How about if Sarah was married?

How about if Sarah was pregnant?

How about if Sarah was married,

and her only sexual partner ever was her husband?

What if Sarah was lesbian

or bisexual?

How about if Sarah were

a gay man?

How about if Sarah was Caucasian?

African American? African? Native American? Hispanic? Orthodox Jewish?

Amish? Asian? From any other cultural or ethnic group?

Please take a moment to

examine your preconceptions about each ethnic/cultural group and HIV.

These are important questions

because HIV and AIDS elicit a powerful counter-transference. It is

essential to explore our own selves as honestly as possible to be able

to be present and compassionate for our clients.

I

nodded in agreement, not escaping to 'therapist neutrality' but trusting

that Sarah had dropped to that wise center within herself. Sarah still

did not want to go to the clinic to get tested. Fortunately we lived

in an area that offered anonymous HIV testing.

If you are unsure of where

to locate anonymous HIV testing, do an internet search now! Go to

your search engine and type in "anonymous HIV testing", using the quotes

to get all three words in the search.

I

was going through my own parallel process with Sarah, as we so often do

with our clients. I was recalling my own HIV test and all the anxieties

and fears which were elicited. Surprisingly, Sarah never once asked my

HIV status during the course of treatment. I think, initially, she

was afraid of what the answer would be. If I was HIV+, that would

be too overwhelming for her. If I wasn't, how could I understand

what she was going through? You might want to stop and consider for

a moment how you would respond if a client asked you about your HIV status.

I also was remembering an

earlier time, before HIV was discovered, when the only decision was to

take an AIDS test or not. There was no treatment. If the AIDS

test was positive, it was a death sentence. The good news is that

if you or your client is HIV positive, there is now treatment available.

When a virus

infects your body, certain cells make proteins called antibodies, which

attack the virus and try to keep it from spreading. The HIV test detects

these antibodies to the HIV virus. It can take the body up to six months

from the time you become infected by HIV to develop antibodies to the virus.

During this "window period," you should realize that, even if your HIV

test is negative, you could still be infected with the virus.

Knowing this fact can

save lives! People unclear on the window period can have HIV, test

negatively, and expose others. Please make sure that you understand

it; so you can educate your clients who have a negative test prior to the

time period for the antibodies to appear before they go on to expose other

partners.

My job

was to help Sarah manage her anxiety and to face the unknown. I knew

that the uncertainty she was facing around the HIV test results would pale

in the face of the uncertainty of a positive HIV diagnosis. Yet,

each of us, every day, faces the unknown. Is today the day we die?

It is exhausting to live on this edge; so mostly we forget. We go

unconscious about the uncertainty of life. It is a great mystery

when we die. Sometimes it takes a jolt, a lightning bolt such as

an HIV test, to wake us up, to ponder the great mysteries of existence.

Testing

What kinds of tests are available, and how do they work?

It can take 3 to 12 weeks (21-84

days) for an HIV-positive person’s body to make enough antibodies for an

antibody test to detect HIV infection. This is called the window

period. Approximately 97% of people will develop detectable antibodies

during this window period. If you get a negative HIV antibody test

result during the window period, you should be re-tested 3 months after

your possible exposure to HIV.

It can take 2 to 6 weeks (13 to 42 days) for a

person’s body to make enough antigens and antibodies for a combination,

or fourth-generation, test to detect HIV. This is called the window

period. If you get a negative combination test result during the window

period, you should be retested 3 months after your possible exposure.

It can take 7 to 28 days for a NAT

to detect HIV. Nucleic acid testing is usually considered accurate

during the early stages of infection. However, it is best to get an

antibody or combination test at the same time to help the doctor

interpret the negative NAT. This is because a small number of people

naturally decrease the amount of virus in their blood over time, which

can lead to an inaccurate negative NAT result. Taking pre-exposure

prophylaxis (PrEP) or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) may also reduce

the accuracy of NAT if you have HIV.How soon after an exposure to HIV can an HIV test detect if I am infected?

The soonest an antibody test will detect

infection is 3 weeks. Most (approximately 97%), but not all, people will

develop detectable antibodies within 3 to 12 weeks (21 to 84 days) of

infection.

Most, but not all people, will make enough

antigens and antibodies for fourth-generation or combination tests to

accurately detect infection 2 to 6 weeks (13 to 42 days) after

infection.

Most, but not all people, will

have enough HIV in their blood for a nucleic acid test to detect

infection 1 to 4 weeks (7 to 28 days) after infection. Where can I get tested?

You can also buy a home testing kit at a pharmacy or online. What should I expect when I go in for an HIV test?

What does a negative test result mean?

If I have a negative result, does that mean that my partner is HIV-negative also?

What does a positive result mean?

If I test positive for HIV, does that mean I have AIDS?

Will other people know my test result?

Should I share my positive test result with others?

It’s important to disclose your HIV

status to your sex partners even if you’re uncomfortable doing it.

Communicating with each other about your HIV status means you can take

steps to keep both of you healthy. The more practice you have disclosing

your HIV status, the easier it will become.

In most cases, your family

and friends will not know your test results or HIV status unless you

tell them yourself. While telling your family that you have HIV may seem

hard, you should know that disclosure actually has many

benefits—studies have shown that people who disclose their HIV status

respond better to treatment than those who don’t.

In most cases, your employer will not

know your HIV status unless you tell them. But your employer does have a

right to ask if you have any health conditions that would affect your

ability to do your job or pose a serious risk to others. (An example

might be a health care professional, like a surgeon, who does procedures

where there is a risk of blood or other body fluids being exchanged.)Who will pay for my HIV test?

Who will pay for my treatment if I am HIV-positive?

Shock

My reactions

were like Sarah's in a way...I, too, did not want it to be true that Sarah

was HIV positive. Whereas she was very shocky, and in denial, I felt

tremendous grief for this young woman. The lines from T.S. Eliot's Four

Quartets "Oh dark dark dark" kept running through my brain. I

knew Sarah would have a lot to deal with over the next few days, weeks,

years, and hopefully decades. I also knew that Sarah's HIV status

would affect Rebecca's life, as well as everyone who knew and loved Sarah.

At this

point, I made a suicide assessment of Rebecca. She had some suicidal

ideation, but no plan. I felt that her love and connection with her

daughter was sufficient to keep her alive. I did, however, make sure

she knew that I was concerned and available to her. I also gave her the

number of the suicide prevention hot-line should she need support and be

unable to reach me.

People newly diagnosed with

HIV or AIDS can feel suicidal, and it is important to assess for this.

This is different from those people who make a conscious decision to end

their lives when an illness is terminal and they are suffering. Please

consult with your ethics board and an attorney for more information on

end-of-life issues.

I went to the HIV Insite website and went

to the section "You

Just Found Out You're HIV Positive."

There is a piece written by Antigone Hodgins,

who was diagnosed with HIV positive when she was 22 years old. She states "The most important

things to remember are:

Sarah

was overwhelmed with her grief, her anxiety for her daughter, and with

the question of when and how she became infected.

HIV DISCLOSURE POLICIES AND PROCEDURES

If your HIV test is positive, the clinic or other testing site will report the results to your state health department. They do this so that public health officials can monitor what’s happening with the HIV epidemic in your city and state. (It’s important for them to know this, because Federal and state funding for HIV/AIDS services is often targeted to areas where the epidemic is strongest.)

DISCLOSURE POLICIES IN CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES

If you are serving time in a jail or prison, your HIV status may be disclosed legally under the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Standard for Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens. State or local laws may also require that your HIV status be reported to public health authorities, parole officers spouses, or sexual partners.

(Source: https://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/just-diagnosed-with-hiv-aids/your-legal-rights/legal-disclosure/)

Several states now offer assistance to people newly diagnosed in letting their partners know of their HIV status.

Some places offer Partner Notification Assistance Program or Contact Notification Assistance Program. PNAP/CNAP counselors can assist the client with HIV in one of three ways:

A PNAP counselor will notify the partner(s) of the individuals infected with HIV directly. The identity of the person infected with the HIV will never be disclosed, nor will location and time.

During a joint counseling session a PNAP counselor will assist an individual infected with HIV in notifying his or her partner(s) .

PNAP counselors can work with people with HIV to give them advice on how to notify their partner(s) directly.

PNAP staff also inform persons with HIV and their partner(s) about the availability of testing and medical services.

Sarah

did not know what to do. "When I think about calling Stan (her ex-husband),

I get really scared. I am so afraid that he will try to get custody

of Rebecca. When I think about getting Rebecca tested, I feel like dying.

And when I think about calling back that witch, Dr. Marten, I shake.

I want to kill her. And I am too afraid to call Joe or Alan (the

two men she had been involved with since her marriage ended); I just don't

know what to do. So, I do nothing. And if Sam finds out, I know he will

leave me. I don't know what to do."

| As the

therapist, what do you do at this point? Do you encourage Sarah to get her daughter tested? What are the ethical implications of her not notifying her past and current partners? How about her health? There are now treatments available for HIV; yet Sarah has not gone to a doctor. Is the therapist, who sits with her and waits for her to be ready, endangering Sarah's life? Sarah was having sex with Sam, a man she hoped to marry. She had not yet told him of her HIV status, although she also had not had intercourse with him since her positive diagnosis and had used latex condoms for some time previous to her diagnosis. How does the Tarasoff ruling apply? What would you do, as Sarah's therapist? |

What exactly does the Tarasoff legal

ruling mandate? In a 1976 case Tarasoff v Regents of the University

of California,it was held that "the right to privacy ends where the public

peril begins" and that "clear and immediate probability of physical harm" to others allows for the breaking of confidentiality. For a discussion

on this, go to "Confidentiality, Privacy, and the 'Right to Know'"

By Lawrence O. Gostin, JD, in which he states, "Is there any principled

way to reconcile the dual obligations of the right to privacy and the right

to know? If

the ethical and legal right to privacy is taken seriously, then it should yield

only where absolutely necessary

to avert serious harm. Accordingly, the right to confidentiality should be near

absolute in cases in which the

risk of contracting HIV is remote....The strongest claim to a right to know

exists where there is an ongoing sexual or needle-sharing relationship. In such

cases, the law should give health care professionals a power, not a duty, to

disclose if,

in their judgment, it is necessary to avert a significant risk of transmission."

Another article, "Physician's Duties to Patients and Third Parties Further

Defined" by Jason

F. Kaar, Maj, USAF, JA reviews recent lawsuits arising from the Tarasoff decision

and HIV and AIDS diagnoses.

It is also advisable to consult with an attorney if you have questions or concerns

about your obligation. Many professional organizations have legal counsel

available who will not charge for a consultation.

ProPublica at http://projects.propublica.org/tables/penalties states that "At least 35 states have criminal laws that punish HIV-positive people for exposing others to the virus, even if they take precautions such as using a condom. Supporters of these laws say they deter people from spreading the virus and set a standard for disclosure and precautions in an ongoing epidemic. But critics say they thwart public health goals because they stigmatize the disease; undermine trust in health officials, who are sometimes enlisted to assist with criminal prosecutions; and fail to take into account the latest science surrounding HIV transmission.

Please check with your professional associations' legal department to ascertain what the law is in your state.

| Now the

clinical picture with Sarah becomes obscured with the legal and ethical

issues. Clinically, she was depressed. She felt frightened

and paralyzed. She was not ready to do anything, until she

came out of her state of shock. However, by not letting Sam know,

she was potentially jeopardizing his life. If Sam was not HIV positive,

he had a chance to protect himself. If he already had HIV, was Sarah

preventing him from getting treatment? Sarah also had an obligation to her daughter, Rebecca. If Rebecca was HIV positive, she could also benefit from treatment. How to handle this? Sarah had never returned the calls of Dr. Marten, the ob-gyn who had suggested that Sarah get tested. I did not want Sarah to quit therapy, yet lives were at stake. I asked Sarah what she was going to do. |

"I don't know!!"

Tears

started rolling down her cheeks.

She

had moved from paralysis into her feelings.

She

cried for a while hunched over.

Finally,

she looked at me.

"I

need to do something, don't I?" I nodded yes. Sarah heaved

a big sigh. "Okay", she said, "I guess I have the whole rest of my

life to figure this out, and to feel all my feelings, but" (and here her

voice get shrill and angry) "if I ever figure out how I got this,

I will kill him. And if Rebecca has it, he is going to be one sorry

dead man!"

Yet,

in switching to anger, Sarah could now take action. She realized

that she had not been given the choice. Whoever infected her did

not let her know he was HIV positive, if he even knew. She did not

want to do that to Sam, as she did not want to carry guilt on top of all

her other feelings.

Sarah

said she would do two things: she would get Rebecca tested, and she would

tell Sam. She decided not to invite Sam to a therapy session.

She would rather tell him herself. She agreed to call if she needed

help.

She

also said she would think about what the counselor at the clinic where

she got tested had said about her options regarding informing past partners.

Anger

Sarah

returned the following week in a towering rage. "I feel like I could

kill Sam, Joe, Alan, Stan...it is no fair and it is horrible!

I keep feeling like a volcano erupting. I can't sleep. I am burning

up." She said that she had started to tell Sam, asking if he knew

anyone with AIDS or HIV. "We were at home, Rebecca was at her Dad's

house. I brought it up, kind of casually. Except I was shaking like

a leaf. So I just asked him if he ever knew anyone that had it and

he went ballistic! He started ranting and raving. He

was totally homophobic, saying horrible things about gay men. I couldn't

believe it. I have never seen this side of Sam, ever. He always seemed

so tolerant and easy-going. So, I chickened out. I just couldn't

tell him. And then I made a big excuse when he wanted to make love.

I said I had another yeast infection. And I canceled our next date,

saying I didn't feel well. I don't know what to do. I have

to tell him. I know I do, but I just can't bear doing it. And

I didn't get a blood test for Rebecca either!" Here Sarah crossed

her arms over her chest and just glared at me.

| What do

I do now? Sarah was looking at me very antagonistically and

I feared a repeat of the "shoot the messenger syndrome" that Sarah had

done with Dr. Marten. I felt like I was walking on eggshells.

If I told her what to do, she looked like she would leave therapy and never

return. Yet, I also felt that lives were at stake: Sarah's

if she didn't get treatment, perhaps Rebecca, if she was HIV positive,

and Sam. I quietly asked Sarah how I could help her. She burst into tears. |

"I

was so afraid that you would yell at me or tell me how irresponsible I

was being. I feel all these things and mostly really, really stupid

for thinking this could never happen to me. The thing I want you

to do I know you can't do, which is to make it all go away...Make it be

the most horrible nightmare and then wake me up."

I too wished I had that power, but I don't. None of us has. |

Sarah continued, "I guess really I am most afraid for Rebecca, that I have killed her life before she ever even had one. What happened is I was going to take her to the clinic, where I went for my anonymous test. We got into the car and she wanted to know where we were going. And I just couldn't do it, taking her to that place with those plastic chairs, and taking a number, and waiting. Then, a stranger would stick her with a needle. So, when she asked me where we were going, I started to cry. And I took her out for ice cream instead. So I guess I just failed everything all week."

We

sat silently for a bit.

Then

I asked Sarah how she was feeling. She started to cry, slumping into

despair. She spoke of sleepless nights and of terrible nightmares

when she did slip into sleep. "Can you believe it...instead of Rebecca

getting into my bed, like she does sometimes, I wanted to get into her

bed!" She was distracted at work and made so many errors that she

said she had a bad headache and went home early one day. I raised

the possibility of medication for her at this time, asking if she wanted

a referral to a psychiatrist for some help with her depression and anxiety.

She looked thoughtful and relieved at the possibility, but decided not

to pursue it at this time. I think my offer felt like an acknowledgment

to her that I sensed how much pain she felt.

"I

feel so alone. No one that knows me knows that I have this awful

thing, except for you."

This image is of David supplicating

God. It illustrates David's lament: Jungians call this time the night-sea-journey or the dark night of the soul. |

Depression

Sarah

came in the following session quite depressed. She had a listless, flat

quality about her. She had not been sleeping or eating, and had dark

circles under her eyes. She reported continued nightmares, a common

theme being swept under by huge tidal waves. She acknowledged that

doing something was better that doing nothing; yet, she did not know where

to start.

| I remembered

reading about the treatment of depression in people with HIV using

a model called 'interpersonal psychotherapy'. This technique emphasizes

mourning losses while encouraging patients to find new goals in life.

A lot of the focus is on living out one's fantasies and to create as full

a life as possible, no matter how much time remains.

I also knew that lives were potentially at stake if I did nothing; so, I became proactive with Sarah. I explained that it seemed there were three really important things she could consider: 1. To explore getting some

medical treatment for herself. |

Sarah looked relieved when I laid out a course of action for her. I supplied her with the name and number of a nearby clinic which specialized in HIV and AIDS treatment, hoping that she would feel less stigmatized there. We called the clinic during our session and made Sarah an appointment.

Sarah had great respect for Rebecca's pediatrician and agreed to tell him of her HIV status and have Rebecca tested by his office. She felt that the idea of Rebecca being tested by strangers would be distressing. She agreed to call his office the next day to set up an appointment.

I was

somewhat surprised when Sarah said that she did not want my help in telling

Sam or her ex-husband or former boyfriends about her diagnosis. She

said that she would go back to the test site, and that she knew already

what she was going to do. She was going to have the counselor inform

her earlier partners that they had been exposed to HIV, but not identify

Sarah. With her ex-husband she was going to tell him, probably at

a joint session with the HIV counselor, but she would wait until she knew

Rebecca's HIV status. And Sam, the almost fiancé? "I

don't know. I have to tell him, but his reaction even to the idea

about HIV was so extreme, it scares me." She decided to also have

him attend a joint counseling session with the HIV counselor. I asked

her why she didn't want to have the joint counseling sessions with me.

She said she needed our sessions just for herself. She agreed to sign a

release so that I could speak with the HIV counselor and with the staff

at the clinic where she was going to seek medical treatment.

If you are in the position to tell someone they have HIV or AIDS or have been exposed, please read:

|

Grief

Sarah came in the following week and as she started to talk, tears appeared. "I have been like this all week, ever since I called Becca's doctor. I just can't stop crying." The doctor had been very compassionate, meeting first with Sarah, then administering a blood test to Rebecca. "He was just so kind." Sarah sobbed. "He kept saying the important thing was that I take good care of myself. That HIV doesn't mean a death sentence, that there is a lot of new medicines now. But now I have to wait for Rebecca's results."

She

continued, "And I went to the clinic that specializes in HIV, and it was

really hard. I sat in the waiting room and figured everyone was staring

at me, that they knew why I was there. Then I realized that is why

they were there too. And all kinds of people, men of course, but

also women. And the saddest thing were the teenagers. They

really have no life. They probably can't ever have kids or anything."

| Sarah

is wrong about the ability to have children when one is HIV positive, but

she is right about the growing group of adolescents and young adults with

HIV.

Any clinician working with adolescents

needs to be familiar with the special issues of teenagers and HIV.

Please go to |

Sarah continued, "They were nice at the clinic. They asked me about depression, told me about the type of medicine that would help, and asked me if I wanted to join a group of people that had HIV. And they had lots of groups to choose from; newly diagnosed, women of color, young adults, all women's groups, men's groups, gay men's groups. They even have one group in Spanish for women who all got HIV from their husbands. It is so sad, but all these groups made me feel less alone."

"And they said to not delay in contacting the HIV counselor, to get help in telling Sam, Joe, Alan and Stan. They were kind of stern about me not yet telling, even though I haven't had sex since I was diagnosed. They said I had to tell or they would. So I called, and the counselor is anonymously notifying my old boyfriends, and Sam and I have an appointment next week. I just told Sam it was for couple's therapy, and he's meeting me after work and we'll go in one car. Actually, maybe we should go in two cars as I am not sure he'll want to ride back with me. And there is no sign on the building, so he won't know what it is about 'til we get there."

"At

the clinic I had to fill out this huge questionnaire, of all the stuff

I had done. The only "high risk" stuff I have done was unprotected

sex. It still seems so unfair that I have this stupid thing. And

I guess now that I am taking action, the fear of death is really big.

I think all my shock and being overwhelmed, and wondering how to tell,

I was just pushing away two really big things. One is where did I

get HIV, and the other is death....."(here Sarah's voice got very soft;

she sounded like a very little child) "I am so afraid of dying."

| Sarah was ready to talk about her greatest fear: death. While HIV is not an immediate death sentence, it is to be expected that she will look at death and feel its presence more acutely. I have had friends and clients with HIV and AIDS who believed that these diagnoses were in fact a "life" sentence", not a death sentence. Alan articulated it very well when he said, "When you live all the time with 'death on your left shoulder', like Don Juan used to say, every moment is much more meaningful. Once I got over the terror of death, I live each day more fully. Each sunrise is somehow more amazing, knowing the ones I see are limited. In fact, that is true of everyone, but not everyone realizes it." Douglas, HIV+, told me "It is a paradox...I am actually healthier now with HIV than I ever was before. I don't do drugs, or smoke or drink anymore. I see a nutritionist and I get regular exercise and try to get enough sleep every night. It is so strange in a way, to have to get so sick in order to get well." |

| Sarah

was not ready to do it at this point, but over the next few months actively

did investigate what kind of death she wanted. She was able to fill out

an "advance medical directive" that specified the amount of care she wanted

if there was no hope of prolonging her life. She also made out a

"living will" and gave copies to her physician. For more information

on this, go to |

Hope

Sarah

came in the next week seething. "I went to the session with Sam,

and I know I got it from him! I just know it! When the counselor

started talking about HIV, Sam again started all that homophobic stuff,

then he got up and started to leave. The counselor stopped him by

asking what his story was. He got real embarrassed, then said a lot

of men who have sex with men aren't gay. Then he left! He just

walked out and I haven't seen or heard from him since. I just know

he gave me HIV."

| In fact, Sarah doesn't know

she got it from Sam. She may never know the source of her exposure.

Any of her former lovers might have exposed her, having themselves been

exposed through sexual contact, either hetero- or homosexual, through drug

use, or through blood products. Sam's reaction was telling, however.

There are many people who have sex with partners of the same gender who

do not identify themselves as gay, lesbian or bisexual. If you are

interviewing someone, or assessing HIV risk factors, it is important to

ask very specifically about sexual partners. I also had to assess the Tarasoff implications here, as Sarah had said earlier that if she ever found out who infected her she would kill him. In the session, we explored her feelings of rage and betrayal. She realized that she did not know with certainty that Sam had infected her. She also didn't know really whether any of her lovers had used IV drugs, received blood transfusions, been sexually assaulted or been exposed to HIV in their earlier relationships. Sarah said that while she felt like killing Sam, that of course, she would not. |

Sarah's two previous partners, Joe and Alan, were notified by the counselor at the clinic that they might have been exposed to HIV. The source of their possible exposure, the time and location, would not be disclosed to them. We discussed a bit how painful it must be to receive that kind of call. Sarah felt badly they would hear it from a stranger, but realized her reserves were too low to meet with either man at this point.

Sarah got the wonderful news that Rebecca was not HIV+ from the pediatrician, who continued to encourage Sarah to take care of herself.

She

met with Stan, her ex-husband, on her own, afraid that he would react like

Sam had done. "I told him, and he was so concerned. He actually

started to cry; he was crying for me." Sarah was able to tell

him that Rebecca did not have HIV and expressed her fears that he would

go for full custody of their daughter. Stan reassured her that the

custody arrangements would not change. He actively encouraged Sarah

to be proactive in getting medical treatment and offered to go on the Internet

to find resources for her. Stan said he did not need an HIV test

as he has been tested recently at the request of a woman he was dating.

The test was negative, but he said he was so nervous that he vowed to have

"no wet sex" (exchanging bodily fluids) with anyone unless they both tested

negative initially, then 6 months later, and then only if they were both

monogamous.

Stan introduced

Sarah to a website called ![]() THE

BODY: An AIDS and HIV Information Resource. Sarah read:

THE

BODY: An AIDS and HIV Information Resource. Sarah read:

Squaring off against HIV means preparing for the battle of your life. There are several steps you can take right now to fight this disease and live better in the process. They include:Sarah also learned from this website that "Women are one of the fastest-growing groups diagnosed with AIDS. Women now constitute 20% of all newly-reported AIDS cases in the U.S. and 42% of cases worldwide --nearly triple the number ten years ago. In the developed world, women are about eight times more likely to become infected from an infected man than the other way around, and thus are very vulnerable to HIV infection." She said she felt less alone when she read that.

- Taking charge of your own life and health;

- Finding the right doctor and learning to work together effectively;

- Exploring the range of treatments;

- Deciding whether, when, and how to tell others; and

- Learning to live with HIV (emphasis on living).

FromFirst Steps: Testing Positive and Taking Charge

Sarah and Stan starting more active 'co-parenting' as a result of their conversations around Sarah's diagnosis. They both made wills, and began to talk about 'disclosure', which is what, when, and how they would tell Rebecca about Sarah's HIV status.

Together they met with Rebecca's pediatrician, who suggested that they wait for Rebecca's questions and then answer only was she was asking. He reminded them that children have different levels of understanding at each developmental level, and for Rebecca to hear now, when Sarah was asymptomatic, that her mom was ill, would be very confusing. He also said that children are egocentric, which is necessary for development, and that Rebecca might blame herself for Sarah's illness. "Wait", he counseled, "and hope that by the time she needs to know, that there is a cure." He did say that when Rebecca was an adolescent to emphasize abstinence and sex education. He said there was a lot of information available now for teenagers. He makes sure all the adolescents in his practice are aware of HIV and how it is transmitted. "With teenagers, you can't really wait for them to ask because by then it might be too late."

Sarah

had less success with her parents. Her father and mother both blamed

her and kept reminding her that they had never approved of her divorcing

Stan. (They seemed to conveniently forget how much they had opposed her

marrying Stan as well). They needed to be educated about the transmission

of HIV, a fact which Sarah realized when she visited them and they sprayed

every surface that she touched with Lysol.

I was remembering my client George

and his parents' reaction to his AIDS diagnosis. George was gay and

had never come out to his Southern Baptist parents. When it was clear

that he was very ill, he contacted them to let them know he had AIDS and

was dying. His father went into a rage and never spoke with

him again. His mother flew out to his side and was holding him when

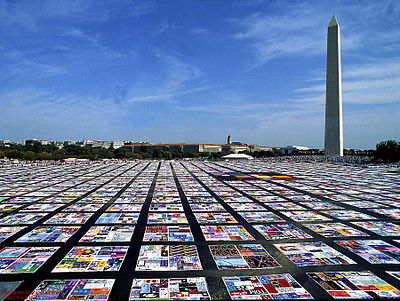

he died. She later helped his lover make a square for the The Quilt, or Names Project, was started in San Francisco in 1987. At that time many people who died of AIDS-related causes did not receive funerals, due to both the social stigma of AIDS felt by surviving family members and the outright refusal by many funeral homes and cemeteries to handle the deceased's remains. Lacking a memorial service or grave site, The Quilt was often the only opportunity survivors had to remember and celebrate their loved ones' lives. It now has more than 48,000 panels and 94,000 names; a growing testament to the deadly toll that AIDS has taken on the world. It weighs 54 tons, and is the largest community art project in the world.  |

Sarah was distressed by her parents' reaction, but got a lot of assistance from the support group she joined at the clinic whose specialty was HIV and AIDS. She chose to join a women's group because initially she was too angry with men to attend a mixed group.

Sarah

was very pleased with the medical care she was receiving at the clinic.

She never returned to Dr. Marten, the ob-gyn who had first suspected that

Sarah was HIV+. It is beyond the scope of this course to discuss her medications

as this field is rapidly evolving. She would talk about her T cell

count (for medical terms, go to the Glossary of the ![]() JAMA

HIV/AIDS Information Center). The fewer

T cells in a count the more likely a person will develop opportunistic

infections or malignancies. A T cell count of 200 cells or

less per cubic millimeter of blood is a diagnostic criteria for AIDS.

There are currently 26 opportunistic infections and malignancies, which

combined with the presence of HIV, meet the criteria for AIDS. These

are called "AIDS indicator illnesses" by the

JAMA

HIV/AIDS Information Center). The fewer

T cells in a count the more likely a person will develop opportunistic

infections or malignancies. A T cell count of 200 cells or

less per cubic millimeter of blood is a diagnostic criteria for AIDS.

There are currently 26 opportunistic infections and malignancies, which

combined with the presence of HIV, meet the criteria for AIDS. These

are called "AIDS indicator illnesses" by the ![]() Center

for Disease Control and Prevention.

Center

for Disease Control and Prevention.

At

the clinic, Sarah began treatment with newly developed drugs for HIV, combined

with stress reduction and nutritional counseling. On her own she

explored alternative medicine, including homeopathic treatment and work

with a naturopathic physician. She has remained quite healthy, after

a scare in which she developed a sudden respiratory illness. She

panicked and it was only after most of Rebecca's first grade classmates

also got sick that she realized it was one of those viruses that spread

like wildfire throughout schools. Sarah had a quick recovery, but

the incident made her realize how vulnerable she feels about her health.

She has had some unpleasant side effects from the medicine she is taking

and her support group has been very helpful with sharing their own experiences

and suggestions.

| I remembered Mike's journey

with AIDS. After the first bout of pneumocystis